From the archives: From the Dissertation to the Book: Going Home

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on April 29, 2021:

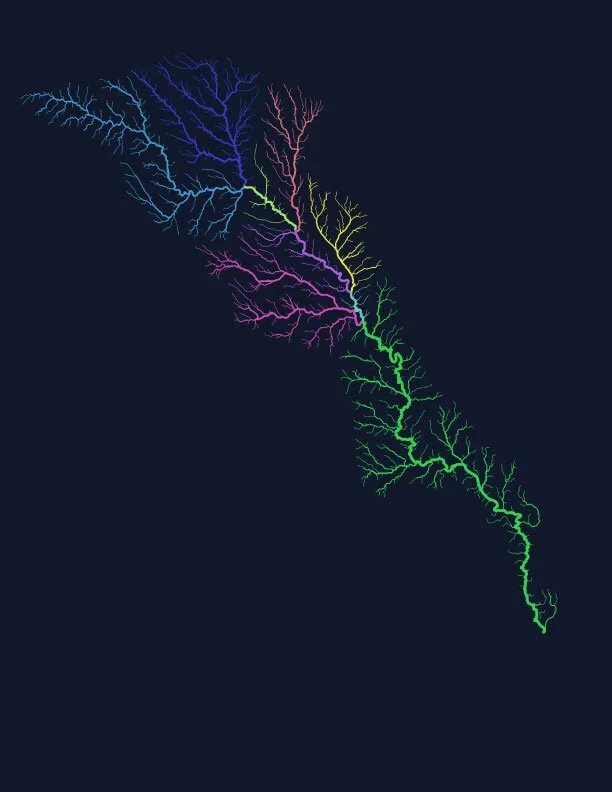

Now that I have deposited and defended my dissertation, it’s on to the next task: writing the book. My main strategy for this year will be to think about it as little as possible and focus on our projects like my river history website. When I do return, I have to figure out how to keep people’s attention who are not my committee or friends as we explore 150 years’ worth of history. I will make many of the same arguments that I do in the dissertation about the environmental and political legacy of slavery, but above all else, this will be a story. And the main character, that will tie everything together and that will undergo the greatest change has to be the Trinity itself. Right now, the Trinity appears in the introduction and early chapters and mostly disappears in the final chapters.

Over the last seventy years, the Trinity has been largely forgotten with fewer people living and working in its floodplain. It has also been a time of dramatic change for the river, and not just because of climate change. The Trinity has also become an even more fearsome place—a fact reaffirmed by several people who have read this very website and share stories of death and loss related to the river. Not everyone can afford to forget the river.

I have been lucky enough to have Bill deBuys, whose writing on rivers is a model for me, mentor me through this final year and he has been the most insistent on this point about the river as a character. One suggestion was that perhaps I needed to organize a trip down the Trinity that would give the book a structure. This sounds like a great adventure, but who knows when my career and fatherhood might allow for such a journey. I do already have a lifetime of experience to draw from.

Though I have not lived full time near the Trinity since I was a boy, I return there regularly to visit my father and be in the country. On the drive from the DFW airport, we exit the interstate onto US highway 287. The Trinity used to close the highway pretty regularly due to flooding, but when I was in high school, they raised the roadbed by a few feet, and at least for now, that’s been enough to keep commerce flowing. Near the end of the two-hour drive we cross the river. As we approach the bridge my dad always rolls down the windows and the Trinity air hits you at seventy miles an hour, its rich smell and humid feel. The odor is so familiar that it simply smells like home to me. I suppose this is a challenge that many authors face, it is much easier to describe new experiences rather than the ones that have become a part of us.

From the Archives: Sickness on the Trinity

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on May 11, 2020:

Of the many prisons in Texas, the Beto Unit, located near the Trinity River has the largest outbreak in the state. Though COVID-19 is a new and terrifying disease, there is a long history of outbreaks along the Trinity River. In the antebellum period, perceptions of the healthfulness of the Trinity varied by location, whereas following the Civil War the Trinity developed a reputation as being generally unsafe for human health. William Bollaert’s report from the early 1840s singled out the Trinity below Swartout as being especially unhealthy: the fevers “common on these low alluvial lands." Ten years later another traveler across the Trinity similarly noted, “Great country here for chills." That same year a plantation mistress wrote to her son describing the fever on their Trinity plantation that quickly took the life of “poor little Flora.” With such conditions, she asked, “Who can tell what a day may bring forth?” Steamboats navigating the river not only carried cash crops but could also spread disease and devastation. In the 1840s one traveler had noted that the Trinity River town of Cincinnati “comes in for its share of agues.”As a thriving river port, Cincinnati had another vulnerability: contact with distant towns from which yellow fever could be spread. The Trinity’s use as a highway to market meant that it could also help spread yellow fever. Once yellow fever arrived in Cincinnati it spread and persisted because of the abundant mosquitos living in the bottomlands. Many, possibly hundreds, died during the epidemic and Cincinnati permanently lost even more of its residents who left and never returned to the promising, but too dangerous river town.

Well before emancipation explorers, settlers, and boosters had debated about the propensity for disease in the Trinity River bottomlands. When the naturalist arrived with Mier y Teran’s expedition at the flooding Trinity he had become so feverish that he no longer cared to study nature. As the historian Conevery Bolton Valencius has argued, nineteenth-century settlers understood, through “universal experience that disease was associated in powerful ways with moist, swampy places.” However, knowing that they were more likely to catch a fever or another illness in the bottomlands did not stop people from moving there. “Settlers confronted the irony of good situations: proximity to waterways, so necessary for economic well-being, meant proximity to miasma and deadly ills,” Valencius writes. Planters who came to the Trinity did so with a combination of wishful thinking and trial and error. If a particular location proved too sickly or too flood-prone then they might move their home. George T. Wood the second governor of Texas and a Trinity planter decided that his first home had been built too close to the river and began building a home on a hill away from the river. Furthermore, planters also came to the Trinity believing that their slaves were less likely to become sick, an idea that played into their racist justification for slavery—and these ideas about race and the environment persisted in the postwar period as well.

Because of their limited resources and minimal aid provided by the federal government, the Civil War and the immediate postwar years were particularly lethal for freedpeople throughout the South. Historian Jim Downs has shown how much suffering and death took place alongside the arrival of emancipation. With the federal government slow to offer aid in the immediate moments after emancipation, Downs writes that “tens of thousands of freed slaves became sick and died due to the unexpected problems caused by the exigencies of war and the massive dislocation triggered by emancipation.” As Downs argues, migration and displacement proved deadly, suggesting another reason why many freed slaves chose to remain on or near their plantations adjacent to the Trinity. Yet with their crops weakened or destroyed by flooding in the first two years after emancipation, freedpeople also faced potential disease with little to sustain them.

When yellow fever returned to the Trinity after the Civil War it had a particularly devastating effect on the freedpeople in the region. Not only were they suffering from failed crops and a complete lack of freedom dues, but yellow fever also hindered the ability of the Freedmen’s Bureau to provide assistance and protect their rights. In 1867 hundreds of United States soldiers died from yellow fever and that September the commander of the Bureau in Texas, Charles Griffin died from yellow fever. In Walker County, a former agent, who had been a voter registrar, died. His replacement survived the disease but found himself unable to follow through on his duties during his illness. Even further upriver in Anderson County, the agent reported on the chaos caused by the spread of the disease.

Given all of the challenges of Reconstruction, the yellow fever outbreak made it even more difficult for the Freedmen’s Bureau to accomplish its mission in a region where white residents attacked agents for doing their job. Most of the freedpeople had arrived at the Trinity before emancipation, and the floods and sickness that came with life on the river appeared as a threat to their survival. Conevery Valencius has argues that 19th century settlers understanding of their bodies and environment played an important role in the expansion of the United States. “That a stretch of land was ‘healthy’ held significance not only for the future of the household that claimed it,” she writes, “but for the future of the nation dependent on such successful settlement.” While Valencius was referring to the physical expansion of the United States, the massive expansion of the federal government and its role in citizens’ everyday life during the Civil War and Reconstruction also depended on healthy environments that would allow its officers and agents to do their work.

1 William Bollaert, William Bollaert’s Texas (Norman: Published in co-operation with the Newberry Library, Chicago, by the University of Oklahoma Press, 1956), 110.

2 Entry from May 31, 1853, Henry H, Field Diary, Box 2003-019, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

3 “Letter from S.W. Goree to Thomas J. Goree,” March 20, 1853, Newton Gresham Library, Sam Houston State University, Digital Collections, https://digital.library.shsu.edu/digital/collection/p243coll3/id/2907/rec/9.

4 Bollaert, William Bollaert’s Texas, 292.

5 D'Anne McAdams Crews, ed., Huntsville and Walker County, Texas: A Bicentennial History (Huntsville, Texas: Sam Houston State University, 1976). Heather Hornbuckle, "Cincinnati: An Early Riverport in Walker County," Texas Historian, March 1978.

6 Conevery Bolton Valencius, The Health of the Country : How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 80.

7 Valencius, 140.

8 Sue Ann Hayes Cobb ed., Hayes Cemetery Patrick Hayes Texas Pioneer, unpublished manuscript 2005, Madisonville Public Library, Madisonville, Texas.

9 S. H. German, "Governor George Thomas Wood." The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 20, no. 3 (1917): 260-68. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30234712, 273.

11 Jim Downs, Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 7.

12 Patricia Smith Prather and Jane Clements Monday, From Slave to Statesman: The Legacy of Joshua Houston, Servant to Sam Houston (Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 1993), 101.

13 Christopher B. Bean, Too Great a Burden to Bear : The Struggle and Failure of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Texas (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016), 144.

14 Valencius, The Health of the Country, 260.

From the Archives: Digital Trinity River History

Grasshopper Geography’s Trinity River

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on April 19, 2020:

Today I launched the latest river history on riverhistories.org featuring none other than the Trinity River. No doubt creating a storyboard about a river that I have spent the past six years studying took less effort than one for rivers about which I had little prior knowledge. One particular piece of advice I received was that I should be careful not to give away all the best parts of my dissertation. I can understand this sentiment that you may want to have people wait to read your published articles or books, but I am also not sure what 'saving the best parts' would even look like. Ultimately my Trinity storyboard reflects change over time from the early 19th century to the mid-20th century and there is only so much one can do in a 15 slide storyboard versus a three-hundred page dissertation/book. Still, this advice made me think what am I "giving away" with this dissertation at any point from the storyboard to the book.

In part this is a question of labor, or six years of my life spent researching, interpreting, and writing. The only way to make an effective argument about this particular river and southern rivers more broadly was to learn everything I could possibly find related to the river. I often frustrated archivists when I told them that I would look at anything they had related to the Trinity River. The research for this project ended up taking me to over fifty archives, including digital ones like the Portal to Texas History, in addition to all the historical commissions collections, state and university libraries in Texas. I found credit reports detailing Trinity River planters and merchants at the Harvard Business School, Cornell had a striking collection of letters from a Trinity River planter to his family in Massachusetts, and even Columbia's Rare Book and Manuscript Collection had useful sources. Then, the next challenge was what to do with these thousands of documents I collected.

In part, I made sense of my research by comparing it with the existing scholarship on the history of rivers and slavery. Thus I read as many history books related to environmental history, the history of Texas, and the history of slavery as possible. And I decided that quite simply, there is not enough history out there that brings together the history of the environment/rivers and the history of slavery. Furthermore some of the more successful books that do explore this relationship such as Mart Stewart's What Nature Suffers to Croe focus on different parts of the South such as the Georgia lowcountry rather than the frontier of slavery. So my work brings together the history of rivers and slavery in Texas and that in itself is an argument about what we need to focus on.

My dissertation has gone from around five chapters to now ten chapters, and most chapters make their own contribution to our understanding of American history. For example my dissertation shows how planters did not assume they controlled nature in Texas unlike the rice planters of the lowcountry--the control of people and nature did not go hand in hand on the Trinity. At the start of the twentieth century, I argue that townspeople played a key role in preserving access to the commons. This claim stands in contrast to major books like Steve Hahn's The Roots of Southern Populism that point to a conflict between towns and rural people as leading to the closing of the commons. And in the middle of the twentieth century I argue that rural people actively advocated for their environment in very significant ways even if their motivations differed from the people typically labeled as environmentalists. So if you have a stake in environmentalism or common lands or the relationship between the exploitation of people and places then this dissertation then you might find my arguments useful.

And finally, the format of my project speaks to ways in which the pieces are less than the sum total of the book. I am trying to build upon past river histories to make a narrative of the Trinity that brings the role of the river to the forefront in a new and compelling way. I hope that this will not only be a dissertation that some historians find useful, but a book that many people who care about river and justice will want to read.

From the archives: Fear the River: Drownings in the Trinity River

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on January 7, 2020:

I've already discussed two major ways in which people feared the Trinity River, in previous posts I described how people often assumed the worst about the creatures and crimes in the bottomlands, with tragic consequences. And much of the dissertation explores how floods dictated the rhythms of daily life. However, my students in my "Rivers, Politics, and Power" course reminded me of another way in which people have feared rivers, mainly through the risk of drowning. During my research for this dissertation I came across countless accounts of drownings in newspapers, journals, and legal documents. At a certain point, I stopped cataloging reports of drowning because the reports were so prevalent.

Over the last two centuries I believe that somewhere around a hundred people died from drowning in the Trinity River. They died running away from slavery. They drowned bathing in the river. They died swimming to ferries tied to the wrong side of the bank. In the 19th century they drowned on sinking steamboats and in the 20th century they drowned clearing snagged trees in order to make the river navigable again.

I pay close attention to these events in the first half of my dissertation. Because word spread about deaths in the Trinity, most people whether they were runaways, steamboat pilots, or stock farmers took precautions when crossing the Trinity. One of the things that stands out to me now, is how many of these deaths took place in the 20th century. As bridges were built across the Trinity and people moved away from the bottomlands, it seems there would have been fewer opportunities to drown in the river. Perhaps the fact that so many people nonetheless drowned in the 20th century meant that people who had no experience with the power of the river would have been less cautious or afraid. It also suggests the ways in which the Trinity retained its power, particularly in urban areas where it was generally hidden from sight behind massive levees.

As I mentioned in my recent Dallas Morning News column in November, the most common response I have heard from North Texas residents when I say Trinity River is, "oh, the bodies?" I had assumed that they were referring to the murder victims who had been thrown into the river, but this reflection suggests they have a broader understanding of the Trinity's relationship to death.

Writing a dissertation on a river forces you to pay close attention to language. Rivers are humankind's original metaphor, describing the constant process of change, including life and death. Like other rivers, the Trinity invites its residents to think in terms of allegories. Thus, the Trinity became a stygian river, not just because of the people who did die in the river, but also because they had been taught about the river Styx and were conditioned to think of certain rivers in this way.

Finally, I wonder how this long history of people unable to counter the power of the river played into opposition to the proposed Trinity River canal. If those drownings contributed to an understanding of the foolishness of trying to control such a powerful and unpredictable process. On the other hand, maybe these deaths encouraged the opposite response: we cannot live with such a dangerous river and it must be tamed and controlled.

From the Archives: The Trinity River as a Texas Symbol for the 21st Century

This column originally appeared in the Dallas Morning News on Sunday November 24, 2019

Growing up in East Texas, I used to go with my dad to the Trinity River to practice my aim on sticks floating downriver. However, the steady flow of soda bottles, oil jugs and footballs that came from North Texas was the most fun, since these items responded more energetically to my .22 rifle, jumping in the air if the bullet made contact.

Whenever I flew out of the DFW International airport, I always looked at the landscape below with fear as the roads, big-roofed homes and warehouses seemed to reach further and further into the disappearing countryside. But when I was on the Trinity, shooting at Dallas’ trash, I didn’t think much about what it meant to be connected through the river to this ever-expanding metropolis. Having spent the last six years writing my dissertation on the Trinity River, I’ve since come to recognize the Trinity’s importance to Texas history, especially as a way to understand the changing relationship between rural and urban places in the state.

Before the end of the Civil War, the lower half of the Trinity was regularly navigated by steamboats and had been one of the major economic regions in Texas. The slaves who lived on the plantations that lined its banks grew cotton that was shipped through Galveston to New Orleans, New York and England. As railroads were built rapidly after the Civil War fueling the growth of cities like Dallas, navigation abruptly ended on the Trinity by the 1870s. Within less than a decade the river went from the equivalent of an interstate highway to a county road. The relative isolation that the river then provided proved useful for many of the freedpeople who remained on the Trinity, as lynchings and the rise of Jim Crow throughout Texas limited their ability to live without the threat of violence.

Most of Texas’ population has lived in its cities and suburbs since World War II, even though most of Texas’ landscape remains rural to this day. North Texas has grown both because of and in spite of the Trinity. As a source of water and an outlet for sewage and industrial wastes, the Trinity enabled development. The massive, costly levees have worked to contain the floodwaters for much of the region and made the Trinity into the state’s most populated river.

All the ways the river has been used and engineered by North Texans have made a different river downstream. Not only does East Texas receive Dallas’ sewage and trash on the river, but floods have become more destructive as a result of the upstream levees. With each new impervious surface covering the prairie, such as another housing development, more water is funneled into the Trinity instead of being absorbed into the ground. These changes made many of the traditional uses of the downstream bottomlands all the more economically impracticable.

Today the Trinity remains maligned, in my own conversations and judging by the press attention. It’s mainly known as a dumping ground for bodies or Lime bikes. Yet the Trinity’s potential as a symbol that Texans can embrace for the 21st century remains huge. It is, after all, a product of our shared history, a dynamic and unpredictable process that has changed in response to major themes in Texas history including slavery and urbanization. Furthermore, the Trinity provides a physical connection between urban and rural Texas.

Though political maps suggest rural and urban Texas have been divided into blue or red counties, the same muddy brown river flows through both places. The trash that pollutes the Trinity in North Texas inevitably floats down to East Texas like a never-ending stream of blank messages in a bottle that need no explanation. More concern for the health of the Trinity in Fort Worth and Dallas would mean not only a healthier environment for North Texans, but also a greater concern for the people who live downriver.

From the Archives: Does the Trinity River Connect or Divide Texas?

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on October 31, 2019:

The Trinity River flows through Fort Worth and Dallas before entering the woods of East Texas. These two regions are defined in contrast to each other: North Texas as a booming sunbelt metropolis and East Texas as a rural, southern, and economically stagnant hinterland—yet they exist along the same river. The history of the Trinity River shows how portraying Texas as a divided state, of rural or urban, has worked against the common good for the benefit of a few powerful interests.

On the one hand the Trinity heightened the divide between the city and the countryside because development in North Texas made the lower river harder to control. As roofs and streets multiplied in Dallas and Fort Worth, they funneled stormwater at much higher rates into the Trinity. At the same time these cities built major levees which pushed the floodwaters downstream, making flooding more destructive in East Texas. Pollution made it even harder for people on the lower river to survive: major floods sometime carried the cities’ pollution hundreds of miles downriver, stinking up the bottomlands and killing the fish rural residents depended on for their dinner table.

By the start of the twentieth century North Texas business leaders came to believe that in order to make their homes into great cities that the Trinity would have to be made into a navigable river all the way to Forth Worth. They gave money, influenced politicians, and even started an advocacy group in East Texas that was secretly funded by people like Amon Carter the publisher of the Fort-Worth Star Telegram. These efforts came to a head in 1973 after they had secured federal financing to build a Trinity canal. The only thing needed now was for the counties along the Trinity to approve $150 million worth of bonds to get the more than billion-dollar project started.

In one of the greatest upsets of Texas politics, a coalition of country people, from wealthy oilmen to small farmers, joined with environmentalists and fiscal conservatives to defeat these powerful boosters’ plans to destroy the Trinity. Rural opposition was not only rooted in attachment to place, but in residents’ understanding of the river itself. Whereas the upstream cities had largely confined the Trinity between its levees, the people living downstream had only experienced worsened flooding on the Trinity as a direct result of upstream urbanization. This experience meant that they had a better understanding that a project to canalize the river was both financially and ecologically impractical.

Boosters’ dreams of canalizing the Trinity did not die at the ballot box and they continued to advocate for different versions of the canal in the mid-1970s. Though several East Texas counties voted in favor of the canal, others like San Jacinto county defeated the proposal by much higher margins than in Tarrant or Dallas county. When public hearings were held about the Trinity after their defeat in East Texas, canal boosters tried to label anyone who opposed their plans as urban outsiders, which was particularly ironic given the fact that the movement to canalize the river had long been financed and led by North Texas businessmen. The chairman of one hearing in Houston County asked a woman who opposed the canal, “just for the dickens of it” where she lived before moving to East Texas. Yet she had never moved from anywhere, as she said, “I was born and raised there.”

From the archives: Politics in the City and the Countryside: Bridging the Divide on the Trinity

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on November 7, 2018:

Since I returned from my October trip in Texas, I've been thinking a lot about the rural-urban framework I'm using. Because the Trinity River flows from urban North Texas and down through rural East Texas, it is a great opportunity to consider the ways that the city and the countryside are connected or divided from each other. This was the main topic of the presentations I led, and I tried to be open about the limitations of this framework. For example, the Trinity River does not explain that much about the contrast in North Texas' century-plus boom and East Texas' long term underdevelopment. Another environmental historian has already written a lovely book on the economic connections between the periphery and the core, but there's a lot of work left to be done on the material and political connections. The commentary and narrative coming out of the media after this week's election has highlighted one of the reasons why my research and analysis is relevant today.

One of The Hill's headlines from this morning reads: "America's urban-rural divide deepens." In their telling of the story "suburban voters delivered a stern rebuke to an unpopular president" and "exacerbate a divide between booming urban centers and struggling rural communities." While this sort of analysis has a purpose given our Madisonian apportionment of votes, it leads to facile and unrepresentative assumptions and stereotypes about rural people. Looking at state-level or district-level votes, ignores a great degree of dissent and diversity on the ground. This was certainly true with the way that politics on the Trinity River has been presented.

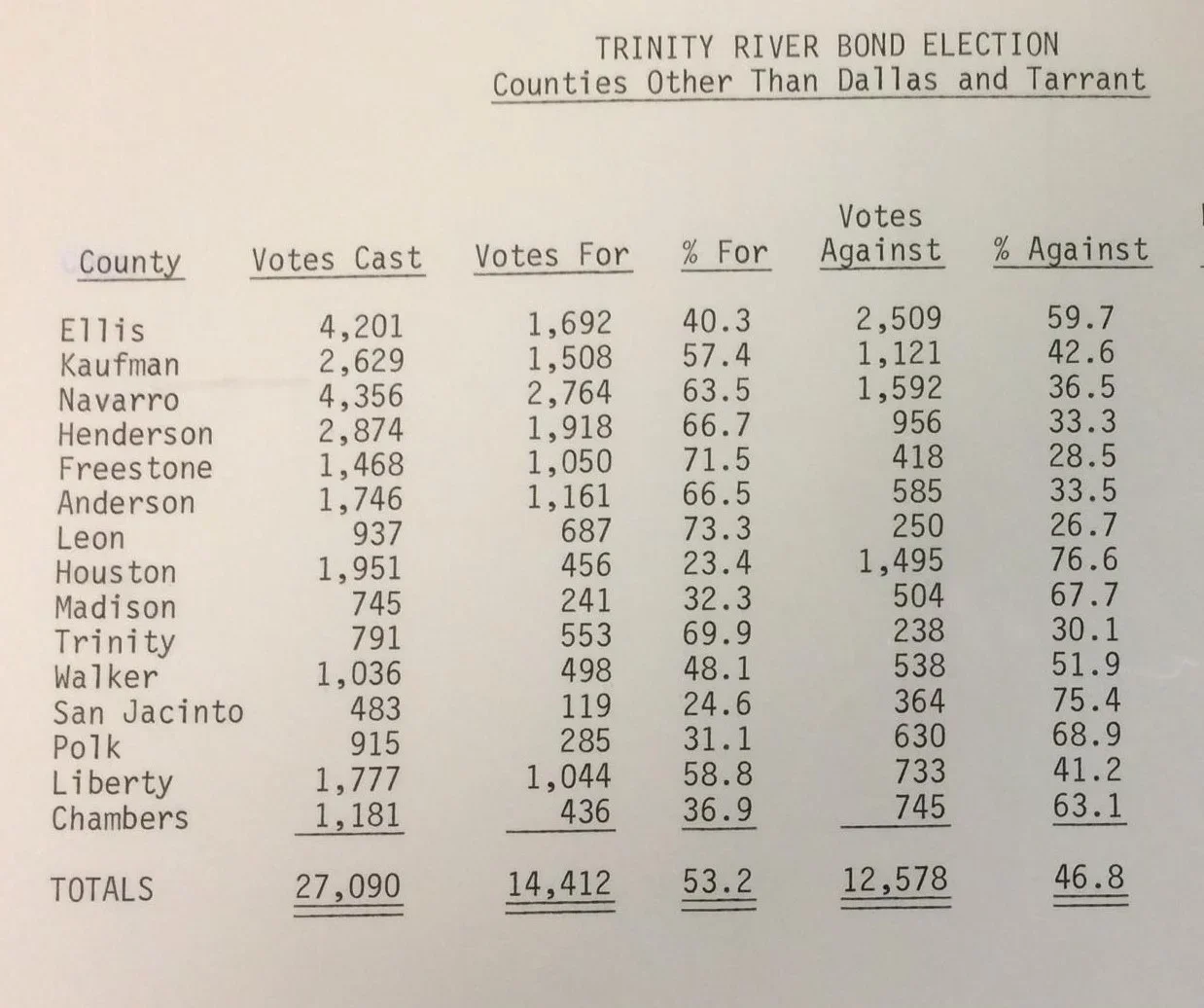

In 1973, all of the counties on the Trinity River from the Dallas-Fort Worth area on down participated in a bond-approval vote to determine the fate of a proposed Trinity River canal. I won't go into all the details here, but the canal was a terrible plan, a waste of money, ecologically ignorant, and not needed, something which even many of its boosters like Rep. Charlie Wilson later admitted. In a surprise to many of the region's most powerful boosters, the canal was defeated. This history is often portrayed as a victory led by urban environmentalists and urban voters. It is true that the urban counties carried the proposal to defeat with 56% opposing in Dallas County and 54% of voters opposing in Tarrant County, but there was significant opposition from East Texas.

As you can see in the attached image, 53.2% of the voters in rural counties voted in favor of the canal. It would be easy for a deadline-crunched journalist to write a similar headline about this vote, ie "Trinity Vote Reveals Gap Between Enlightened Urban Voters and Ignorant Country People." But that's not what the data actually says. Several East Texas Counties voted against the canal, and San Jacinto and Houston County both opposed the canal by over 75%, enough to make the Sierra Club blush with pride. Certainly rural voters and urban voters had different reasons for voting against the canal--but it would be both inaccurate and unfair to label all East Texans as blind supporters of elite boosters and their plans for the conquest of every environment.

In this context, my dissertation reminds me a bit of the new reboot of #queereye, without the laughter and tears. The cast spends a lot of their time working with people who live in rural/exurban regions and who at first glance might fit the portrayal of hateful, intolerant country bumpkins, but then it turns out they're kind and thoughtful people who are willing to learn. Or for my historiographically-minded readers, think of this project as reflecting more of Lawrence Goodwyn's approach in which he wrote, "At bottom, Populism was, quite simply, an expression of self-respect,” rather than Richard Hofstadter who portrayed rural people as angry and left-behind.

Tally of 1973 Bond Vote That Defeated the Proposed Trinity Canal

From the Archives: From Boom to Backwater

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on August 16, 2018:

Wonderful books have been written about the history of Texas rivers and even many of its creeks, though no books have been written about one of the state's major rivers, yes the Trinity! To the west of the Trinity on the Brazos there's Kenna Lang Archer's recent Unruly Waters and to the east Thad Sitton's Backwoodsmen covers the history of the Neches.

Sitton's book, Backwoodsmen : Stockmen and Hunters along a Big Thicket River Valley, describes a world that had long been divorced from the get-rich mentality that powered Texas' growth. From the start of Anglo settlement the Neches was a backwoods, backwater area where subsistence rather than commercial growth proved the rule, but unlike the Neches, the larger Trinity did not start out that way.

As I've been writing the actual dissertation this summer, I have realized the extent to which the Trinity was not peripheral but central to Texas' economic growth in the antebellum period. The Trinity was one of the major plantation regions in the state. It's likely/possible that planters forced more slaves to plantations along the Trinity than any other area in Texas in the five years leading up the Civil War. By the 1850s the Trinity was the place where planters wanted to live--with its navigable river (albeit not always so) and its abundant fertile lands. While the Neches was always a backwater, it's all the more striking that the Trinity went from being so important to the state's growth to becoming a backwater by the 1890s. To a large extent this change happens because of the river. Explaining why and how this happens, especially in relation to the rise of an urban Texas centered around Dallas, will be the much of the work of the dissertation.

From the Archives: The Trinity River Archives

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on March 23, 2018:

During my return from a research trip to UT's Briscoe Center last week, I made a list of all of the archives in which I found sources for my dissertation on the Trinity River. I thought the list would come out to around 30 different archives, but the actual list came out to 37 locations. At some places I only gathered one or two documents whereas at archives like SMU's DeGolyer Library or the Texas State Archives I have collected hundred of images. The list of archives does not include all of the sites I visited, for example I went to the National Archives in D.C. two years ago to study the Freedmen's Bureau records, but have since found all of these sources on familysearch, which is far superior to microfilm. Recognizing the number of archives I have visited has made me realize that I need to start writing soon. Funding permitting, I will take one more research trip this summer. There are one or two new sites I need to visit and several archives that I need to return to because the time period for this project has expanded since I began my research. Also, I need to return to spend more time at the Rosenberg Library in Galveston because on my last visit I had not realized how terrible the traffic is in the Galveston/Houston area and ended up only have about two hours there before I had to leave to catch my flight home! People talk about the expense of global history, but even this river history, within a single albeit, large state, can be quite costly. Funding from individual libraries has been helpful, however research funding not tied to a particular library such as the East Texas Historical Association's Otto Lock grant has allowed me to visit so many of these smaller unfunded sites.

Other than my project's scope, another major change has been the quantity of materials that have been digitized. There are likely several collections that I visited in person which have since been digitized. The single best resource has been the Portal To Texas History-that site is the reason my computer's mouse had to be replaced and I am still not finished reviewing all of their sources, especially their newspaper collections. These online resources have saved me money and allowed me to research more efficiently. I know some people really enjoy being in the archives all day, but I would much rather spend a limited two-three hour period of time doing research each day, which is exactly what all these online resources have made possible.

How did I decide to visit all of these archives? The finding aid's and Texas' TARO (Texas Archival Resources Online) have been useful, but a word of caution to other Texas researchers that a significant portion of holdings are not on TARO even if the archive is listed in TARO, and can only be found on internal catalogs--hence the reason to always make contact with the archivists who will point you in the right direction as long as your project is not hopelessly broad. I have been mining the footnotes of all the relevant secondary sources. One such example is the WPA slave narratives. I thought I had searched through all of these interviews at the outset of my research. Only when I found several WPA quotes in other history books about the Trinity did I realize I was missing something. It turns out that the majority of the interviews from Texas are listed as "supplement" and you will not find them if you download the main set of interviews from Library of Congress/Gutenberg. Maybe you already knew this, but no one told me, and my project would have been much poorer had I not made this discovery.

The reason I visited the manuscript collection at Cornell was because of a citation found in Mike Campbell's An Empire for Slavery. Buried within a much larger collection relating to a Cornell Professor are a series of letters written by Otis Wheeler and his daughter Lizzie. How Campbell knew to look through this collection I have no idea. Wheeler owned a plantation along the Trinity and he describes life along the Trinity, how floods could destroy crops or how fish and river bottom hogs provided food for the plantation. Wheeler had moved to Texas from Lincoln, Massachusetts where his mother still lived. He often wrote about his distaste for the abolitionist sentiments in New England, but he spoke fondly of his old friend Summer Bemis. In 1860 Wheeler wrote his mother, that Bemis, whom he had not seen in twenty years, should come visit, however "if he is an abolitionist any other country would suit him better than this." Wheeler learned in short order about the rise of abolition in the United States. One of my good friends from Concord Massachusetts (the town adjacent to Lincoln) is a direct descendant of Summer Bemis so I guess it's a small world in the past and the present.

List of Archives used:

Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

The Perry-Castañeda Library, The University of Texas at Austin

Texas State Library and Archives, Austin, TX

Sam Houston Regional Library Texas State Archives, Liberty, TX

Houston County Historical Commission, Crockett, TX

East Texas Research Center, Stephen F. Austin College, Nacogdoches, TX

The History Center, Diboll, TX

Palestine Public Library, Palestine, TX

DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX

Bridwell Library, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX

Dallas History & Archives Division, Dallas Public Library, Dallas, TX

Special Collections at University of North Texas, Denton, TX

Portal to Texas History, the Internets!/ UNT

Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX

The Texas Collection, Baylor University, Waco, TX

Texas Baptist Historical Collection, Waco, TX

Trinity County Historical Commission, Groveton, TX

Walker County Historical Commission, Huntsville, TX

Rosenberg Library, Galveston, TX

Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library, Houston, TX

Polk County Historical Commission, Livingston, TX

San Jacinto County Historical Commission, Coldspring, TX

Albert and Ethel Herzstein Library, San Jacinto Museum of History, La Porte, TX

Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, New York, NY

Leon County Genealogical Society, Centerville, TX

Texas Prison Museum, Huntsville, TX

Thomason Room Special Collections, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX

Archives of the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, Livingston, TX

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

The National Archives at Fort Worth, National Archives, Fort Worth, TX

Environmental Research Library, Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, Austin, TX

General Land Office Archives, Austin, TX

Trinity River Authority Archives, Arlington, TX

Trinity River Authority Lake Livingston Archives, Livingston, TX

Crockett Public Library, Crockett, TX

Images posted on original site: https://www.wsmcfarlane.com/blog/2018/3/23/yf2r8injufeudv1fj3xji5fshdx29y

From the Archives: You Can’t Tame the Trinity! What about the dissertation?

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on December 12, 2017:

A few weeks ago I was asked what would be the perfect evidence for my study of the Trinity River and I realized that I had already found it. This past summer after I gave a presentation on the Trinity in Polk County, several audience members shared stories about the river in addition to asking me questions about my research. One comment revealed a key theme of the river and people’s relationship to it. This person described how an old friend had once told him that “you can’t tame the Trinity!”

“You can’t tame the Trinity!" succinctly covers a widespread and long-running understanding of the Trinity held by many East Texans. They understood that neither they nor any outsiders, no matter their capital and expertise, could stop the river from flooding, shifting channels, or doing whatever else it wanted to do. Yet I also think this quote suggests the ways that East Texans understood the river as an allegory for their own lives: You can’t tame the Trinity or East Texas.

By the 1950s East Texas had endured a sustained decline in its agricultural economy that was not fully replaced by scattered oil derricks or a handful of industrial sites. This decline contrasted with a booming Dallas that sent its sewage and worse pollution downstream to East Texas, but this economic stagnation did not translate into a complete loss of political power. Neither the river nor the people died out or became wholly subservient to the rising power coming from the North. In 1973, when Polk County voters helped to defeat the Trinity River Authority’s plan for turning the Trinity into a shipping canal, they sent a message about themselves and their river.

Such evidence may be commonplace, indeed many other people have likely uttered the exact same words: “you can’ tame…” not only about the Trinity but a great number of other rivers as well. Though there are plenty of particulars about the Trinity and East Texas, that’s also the point–many people have long seen their own rivers and floodplains as ungovernable spaces that are best left alone and a significant number East Texans felt similarly about their own communities!

From the Archives: Murder and Floods on the Trinity

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on August 7, 2017:

After I flew into Dallas for my latest research trip, my cab driver’s response to my mention of the Trinity River was: “Oh you mean the bodies?” Whatever renaissance American rivers may be experiencing, the Trinity’s reputation remains infamous. I have a few theories about when and why this reputation developed, but in part it is simply a result of the fact that people did meet their deaths down by the river. One of the first readers of my blog sent me documentation of her family’s history with the Trinity River when her great-grandmother was murdered next to the river on May 20, 1923 at age twenty. What happened, and what does this event tell us about the Trinity River?

Unfortunately most of the older police files have not been archived in the Dallas Municipal Archives, but the newspaper reports confirmed the details of Geraldine Harris’s death. She had come to the Trinity River with friends for a fishing trip near the California Crossing in what is now Northwest Dallas. Early that morning another member of the fishing party “had fired two shots from a pistol at some bushes where he heard a rustling sound which he believed to have been made by a wolf or some other wild animal.” (Dallas Morning News, May 21, 1923) The other term used in the newspaper articles was that the assailant had fired at a “booger” in the bushes. Not until all three men present had armed themselves did they investigate what was in the bushes. Mrs. Harris's husband discovered his wife’s body, “‘My God! You’ve killed my wife!’ Harris exclaimed as he rushed to the prostrate form of Mrs. Harris.” (Dallas Times Herald, May 21, 1923)

One of the detectives assigned to the case was Will Fritz, who forty years later led the investigation into the assassination of JFK. Despite the strong detective work there is no indication that anyone ended up serving time for this murder. According to the reports, the shooter feared a wild animal rather than another human, and he took a shoot-first ask questions later approach. The Trinity would have been a relatively undeveloped area, and it is unclear whether the shooter had a reason to fear the animals along the river or if he had heard tales of these wild animals. In The Making of a Lynching Culture Bill Carrigan argues that the state’s reputation for violence made new settlers more likely to take part in a culture of violence. There may be some specific material reasons why so many murders happened along the Trinity, but a bad reputation and an itchy trigger finger also played their role in this tragedy.

On May 21, 1923 the Trinity made two separate headlines, the first reads: “Jurors Probing Death of Woman Bullet Victim,” but directly below that story the next headline reads, “Heavy Rains May Cause Trinity To Overflow Again.” While the placement of these two stories next to each other may be both conscious and coincidental, it shows the ways that the physical actions of the river and its reputation are completely intertwined. How I put the Trinity’s relationship to Texas culture into words, is one of the many questions I will be trying to answer over the years to come.

From the Archives: What about Ferries?

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on February 23, 2017:

There are two kinds of boats that dominate the historical record of the Trinity River: Steamboats and Ferries. Steamboats makeup the bulk of the collection. If you go to a Texas archive and look under the card catalogue for “Trinity River” there’s a good chance that half of the materials you find will be about steamboats. Like railroads, it turns out that many people are obsessed with steamboats. I don’t share this enthusiasm for steam power, though in future posts I will discuss the other possibilities for interpreting this substantial source base. While not nearly as evident in the archives, I have found quite a bit of information on ferries as well. When I lived and worked in Oregon I used to take the ferry across the Willamette River to work every morning, but that was mostly a choice since there are plenty of bridges that cross most rivers. Rivers used to be constant barriers for travelers who were lucky if they could find a ferryman to get them across and save them a swim. Several years ago at a conference, another historian described how he had read or heard from Don Pisani that we should not think of rivers as bisecting land, but of the land bisecting rivers. I haven’t been able to track down the exact quote, but it really captures a reality for many Texans–fortunately for them however, there were quite a few ferrymen in the 19th century.

But what was life like for these ferrymen? When I was a regular on the ferry, many ferry operators mentioned how bored they were much of the time when only twenty cars would use the ferry all day. Yet many of these 19th century ferrymen had far fewer patrons on most days. Presumably they would have had other activities to occupy them whether that was whittling things, fishing, or who knows what. The coins they collected could have been quite substantial, and some traveler accounts describe how they were not carrying the fare on them and were cursed out by the ferryman. The labor of the ferrymen would also have varied with the river. During low-water periods the span of the river might be only ten yards, while at high water times people describe ferries taking them across for five miles. Would they have charged a flat rate? Sometimes, especially in periods of armed conflict and flooding, the ferryman could get quite backed up, with people waiting for a week to be carried across the Trinity.

From what I can tell, the life of ferrymen was anything but boring. And it could also be quite dangerous. Lawsuits were brought against the ferrymen questioning their skills. And people also attacked, or even murdered ferrymen. Perhaps because they were relatively cash-rich individuals? In one case a ferryman on the Trinity was murdered by an axe-wielding assailant who was hired to kill the ferryman so that another relative could inherit the ferryman’s property.

And what did the ferrymen think about the river? Without it they would have lost a relatively reliable source of income, at least until the bridges were built. As far as I can tell the first bridge across the river was built in Dallas in the 1870s. The ferryman is a bit like the farmer from Faulkner’s The Reiver’s who has his mudhole or the many “mud farmers” of the East Texas oil field who charged passage or dug people out, except in this case the ferrymen didn’t have to build a river…

From the Archives: The Trinity River and Freedom

Originally published at wsmcfarlane.com on January 24, 2017:

What is freedom? For the inmates who live in the prison units along the Trinity River bottomlands in Tennessee Colony the answer is easy: Everything beyond the last razor wire fence. Yet unless they are serving a life-sentence, the passing of time represents a better opportunity at freedom compared with escape into the bottoms. If wet, the blackland mud will collect on their feet, weighing them down and leaving a trail of alien prints in the mud that even a hyposmic hound could follow. As they near the river they will enter the checkerboard woods, so named because these blocks of field and forest resemble a checkerboard when viewed from above. Originally cut with the purpose of making it easy for posted sentries to shoot escaping inmates as they crossed from one block of woods to another, the extensive edge habitat and lines of sight have made it the most productive section of a hunting preserve whose blinds tower over the white-tailed deer and wild boar flushed by the panicked escapees.

Beginning in the 1820s, much of the Texas landscape represented a similarly fraught geography of possibility and danger for those who attempted to escape their enslavement. The end of the Civil War and the ratification of the thirteenth amendment, which abolished slavery, might appear to level the geography of freedom. Yet violence only increased in Texas’ postwar years, and in the years after emancipation freedmen sometimes turned to the floodplains of rivers such as the Trinity in search of freedom. The thirteenth amendment itself contained its own Trojan horse on the question of freedom. It reads: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convinced, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Vagrancy laws and rising incarceration rates suggest how Texas sheriffs used the thirteenth amendment’s prison loophole to limit the gains of emancipation. The thirteenth amendment at once enabled and restricted freedom. A river runs through these tensions, which are made visible on the Trinity River and the plantations, runaway refuges, prisons, and homesteads along its course.

Those freedmen who settled along the river discovered that by breaking down the divide between land and water, by accepting the rhythm of flooding, they could elevate the divide between freedom and slavery and build independent communities. Flooding regulated the kind of crops that could be cultivated, the kind of people who would plant them, and the kind of people who might try and control their labor. Flooding also made rich land, albeit a bit slippery when wet, and cracked like thousands of broken pots when dry. Accepting certain limitations also meant unleashing the tremendous potential of the alluvium and the landscape itself.

Much of the wildlife, including the enormous scaled alligator gar that breathes air, depend on flooding to survive, only spawning when the river breaches its own levees. Understanding the gar as ecological and historical also explains why some people who lived along the river did not see flooding as an aberration or a problem. Like the gar, these river people viewed flooding as a necessary, inevitable process that they must incorporate into their routine, and which inevitably changed their perspective of the world.

However by the beginning of the 20th century, the gar had received the label of trash fish, sometimes left nailed to a tree where it continued to breathe air even as it died of desiccation, and the river had largely ceased to be a region of refuge. The gar and river people never disappeared, but their importance diminished, becoming tokens of prehistory or precapitalism. If anything remains unchanged from the 19th century today it is the always-changing Trinity, which still floods and shifts its banks, more readily than ever as the vast impervious surfaces of the Dallas metropolitan area channel water directly from the sky into the river. Millions of people live with the river’s floodwaters, but they no longer adapt to them. The Trinity no longer directs the shapes of their thoughts or their ideology. The river is no longer a home.

When the river functioned as refuge, its most important quality was distance, the way its forest, mud, and floods kept sheriffs looking to fill work crews out of their homes. In Texas, the violence only intensified starting in and after 1865 and freedmen looked for places where they could keep that violence at a distance. So they did not initially adapt to the river by choice, and they only discovered the benefits of letting fears of flooding dissipate because they had bigger fears to live with. In the Works Progress Administration’s interviews with former slaves in the 1930s, many interviewees spoke fondly of their time along the Trinity, how their families and communities flourished in such places. One man spoke of how they often carried guns to protect themselves from the panthers that lived in the bottoms, but he left unsaid how the necessity of arming themselves against the panthers could also protect his family against the dangers that lurked beyond the river.

Panthers still roam what’s left of the woods along the Trinity–if they’re lucky, the prison escapees might see a mountain lion, which would not attack, but would nonetheless frighten them, raise the hairs on the backs of their necks, and make them feel alive. Running the last yards to the riverbank they’d find a deep, wide, and muddy channel, full of floating debris: sticks, footballs, oil jugs, and soda bottles. There they would have to choose to swim in the swift water with the alligator gar and alligators or keep running along the bank. However unfamiliar and frightening the landscape might be, for a moment at least, they would be free.